Studies Using Emotion as a Dependent Variable Peer Review

1. Introduction

Professional do in healthcare requires a lot of personal and organizational engagement. Nurses perform many different care and handling activities with the principal aim of contributing to the promotion, stabilization, and maintenance of their patients' wellness. Using a wide concept of health [ane], understood equally a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-beingness and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, date becomes a fundamental variable for quality patient care [2,iii,4].

Appointment has been empirically shown to influence nursing performance, with a consequent bear on on health care results [5]. From a psychological betoken of view, engagement leads to subjective wellbeing [six] as it allows an private to enter a period state [vii] and satisfy basic psychological needs of autonomy and competence [8,9]. Previous research in nursing has confirmed a positive human relationship between appointment and cocky-efficacy as well equally chore satisfaction [10,11]. Research has as well institute significant associations betwixt date and personal factors such as mental health, locus of control, and task satisfaction [12,13].

Engagement has been divers by three fundamental dimensions: vigor, dedication, and assimilation [xiv]. Vigor is characterized past high levels of energy and mental resilience in the confront of difficulties and implies endeavor and persistence at work. Dedication is defined every bit being closely involved in 1'due south work, has a cerebral dimension or belief in what 1 is doing, and an affective dimension, related to feelings of enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, challenge, and significance. Absorption is characterized past a state of abstraction at work, experiencing a feeling of enjoyment associated with the want to keep working. In that respect, Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter [fifteen] demonstrated a strong negative association betwixt vigor and burnout, and between dedication and indifference to work performance, indicating these dimensions as corresponding polar opposites. Yet, assimilation is not the opposite to a lack of professional person efficacy, and are two distinct concepts [16].

Studies comparing appointment by gender have produced controversial results, from those confirming the beingness of meaning differences [17,18,19,20,21] to those which found no differences [22] or differences with a small effect size [18]. Where differences have been found in engagement according to sexual activity, the results have not been conclusive. On the i hand, Schaufeli and Bakker [twenty] found that men exhibited greater general engagement and higher levels of dedication and absorption than women, whereas in another study [xix] the reverse was found, with women scoring college than men in overall date, and in absorption and dedication. Various researchers have institute that women scored significantly higher than men in vigor [17,nineteen,23]. In samples of nurses, historic period has been found to be positively related to date, although the associations were weak [18].

We may deduce from this that appointment is function of a nurse's value system, and should be an important objective from an organizational point of view. Personal try and identification with the task can lead healthcare professionals to feel positive emotions and showroom greater satisfaction in patient care. For that reason, if engagement is a key pillar of patient intendance, positive emotions and emotional intelligence (EI) must also be fundamental.

Bar-On [24] stated that emotional intelligence referred to a multifariousness of non-cognitive skills, competencies, and abilities that influenced a person's chapters to succeed in the face of daily demands and pressures. Existence emotionally intelligent implies the ability to accost, sympathise, and feel one's own emotions and those of others, and existence able to respond and human activity accordingly (intrapersonal, interpersonal, stress management, adjustability, and general mood). In a healthcare context, emotional intelligence has been related to lower levels of stress and job satisfaction [25,26,27,28].

In terms of sexual activity-related differences, Liébana et al. [23] establish that women scored significantly higher than men in emotional intelligence. In research analyzing each component of emotional intelligence separately [29], female nurses scored higher than male nurses in the interpersonal dimension. Still, others [30] establish no meaning relationship between sex and scores in the interpersonal dimension in a sample of dental students.

Inquiry into the relationship betwixt other dimensions of emotional intelligence and gender has produced contradictory results. Van Dusseldorp et al. [31] found that female person nurses scored significantly higher than male person nurses in some aspects related to intrapersonal factors. Withal, in another written report [29], male nurses scored higher than female nurses in intrapersonal components and stress management. Similarly, others [30] establish higher scores in male nurses' intrapersonal components, stress management, and mood when compared to female nurses. In addition, in other cases [32] it was found that men scored significantly higher in the adaptability dimension.

Historic period was not plant to be associated with the emotional intelligence of nurses [31], which was in dissimilarity to other results [33], who establish that nurses' empathy macerated with historic period. One study [34] found no significant differences between the emotional intelligence scores in nurses based on demographic variables such as age, sex, marital status, or having children.

Enquiry on the relationship between date and emotional intelligence in teachers [35], in healthcare [36], etc. Ane study [36] found that nurses with higher levels of emotional intelligence or better opinions of organizational fairness tended to showroom greater levels of engagement. In this aforementioned report, the four emotional intelligence dimensions were found to be positively correlated with engagement. In another written report, [37] found that personal resource such as emotional competence were closely related to engagement in nursing, whereas a study of nurses' perceptions most the skills they need to exercise their jobs successfully showed social intelligence to be a predictor of engagement [11]. Some authors [38] suggested that people who were non emotionally intelligent would not exist able to deal with the demands of their jobs and would be more likely to succumb to burnout and reduced commitment, which would cease up affecting their wellbeing at work.

Starting from these premises, and enlightened that engagement in the healthcare field needs high levels of emotional intelligence, we began this study into the relationship between engagement and emotional intelligence in nurses. We proposed the post-obit objective: to determine the explanatory value of the components of emotional intelligence for engagement in a sample of nurses.

We began with the post-obit hypotheses: (i) despite the literature review not producing conclusive evidence, we expected to find differences in emotional intelligence and engagement co-ordinate to sociodemographic variables, principally sex and historic period; (2) nosotros expected to find significant positive correlations between emotional intelligence and engagement in nurses; and (iii) the emotional intelligence dimensions of stress management, mood, and interpersonal gene volition have the greatest predictive value for engagement in nurses.

two. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The initial sample was made up of 2218 nurses from Andalucía (Spain) who were randomly selected from various centers. Nosotros identified 92 cases that were removed from the sample for not completing the whole questionnaire (32 subjects) or because we institute that they had completed it randomly (threescore subjects). As the main variable in the study was engagement, the selection of participants included noting their current working situation (permanent or temporary contracts). The resulting sample was made upward of 2126 working nursing professionals (69.half dozen% with temporary contracts, n = 1479, and thirty.iv% with permanent contracts, n = 647).

The hateful age of the participants was 31.66 years old (SD = half-dozen.66), ranging betwixt 22 and 60 years onetime. Over 3-fifths (84.nine%, northward = 1479) were women and fifteen.ane% (n = 321) were men. Just over 2-thirds of the participants (69.7%, n = 1482) had no children, 13.three% (n = 284) had i child, 14.four% (n = 306) had ii children, and 2.5% (n = 54) had three or more children.

2.2. Instruments

We created an ad hoc questionnaire to collect sociodemographic data (age, sexual practice, number of children, type of piece of work contract).

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) [20]; is a cocky-reporting scale to evaluate appointment at work through 17 items with a seven-bespeak Likert-type response calibration. It produces information nearly three aspects of engagement: vigor (e.g., "At my work, I feel bursting with energy"), dedication (e.k., "I find the piece of work that I do full of meaning and purpose"), and assimilation (e.m., "Fourth dimension flies when I'thou working"). The scale gives an overall date score and a score for each of the specific dimensions. This instrument has demonstrated appropriate reliability and validity [fourteen]. In our sample of nurses, the internal reliability indices in each of the dimensions were very practiced, with a Chronbach's blastoff of 0.84 in the vigor dimension, 0.89 in dedication, and 0.81 in absorption.

The Reduced Emotional Intelligence Inventory for Adults (EQ-i-20M) [39] was validated and assessed by the authors for the adult Spanish population, and derived from the accommodation for adults of the Emotional Intelligence Inventory: Young Version (EQ-i-YV) from Bar-On and Parker [twoscore]. It consists of twenty items with iv response alternatives in Likert-type scales. Information technology was structured as 5 factors: intrapersonal (area that includes the following components: emotional understanding, of self, assertiveness, cocky-concept, cocky-realization, and independence; e.yard., "I can depict my feelings easily"); interpersonal (empathy, social responsibility and interpersonal relationship; e.g., "I sympathize well how other people feel"); stress management (stress tolerance and impulse command; e.grand., "I find it hard to control my acrimony"); adaptability (proof of reality, flexibility and problem solving; e.thousand., "I tin solve problems in different means"); and general mood (happiness and optimism; e.g., "I feel good about myself"). Cronbach'south blastoff for each of the scales was: 0.90 for intrapersonal; 0.75 for interpersonal; 0.82 for stress direction; 0.82 in adaptability; and 0.87 for full general mood.

2.3. Procedure

Prior to collecting data, we assured the participants that the treatment of data in the report would comply with applicable standards of data security, confidentiality, and ideals. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Almería (Spain) (ethic lawmaking: UALBIO2017/011). The application of the questionnaire was washed through a web platform which immune subjects to complete them online. A serial of control questions were included to monitor for random or incongruent responses, which were removed from the written report.

2.4. Data Analysis

We confirmed the univariate normality of the sample following the criteria in which the maximum allowed values for asymmetry and kurtosis are ii and seven respectively, and the multivariate normality whit the apply of Kolmogorov–Smirnov, obtaining values greater than p < 0.05 in all the variables. We first analyzed sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, and number of children. To identify significant differences between men and women, we used the Student's t-test for contained samples of the components of emotional intelligence and for each dimension of appointment. In club to place the relationships between those variables and the subjects' ages and numbers of children, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient.

In club to understand how the predictor variables (emotional intelligence: intrapersonal, interpersonal, stress management, adjustability, and general mood) related to the criterion variable (engagement: vigor, dedication, and absorption), we performed a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis. Finally, nosotros performed a nonlinear predictive CHAID (chi-foursquare automatic interaction detector) regression and constructed a nomenclature tree. In order to do so, we used the median date score (Md = 11.67) from all items. Scores below 11.67 were included in the low engagement grouping, and scores greater than or equal to xi.67 were included in the high date grouping. All analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) statistical software for Windows. Finally, to identify mediation models for estimating the effects on engagement dimensions, a simple moderation assay is carried out for each of the cases. To practice this, the SPSS macro was used to compute models of simple moderation furnishings [41]. In addition, the bootstrapping technique with estimated coefficients from 5000 bootstrap samples was applied.

3. Results

three.1. Emotional Intelligence, Engagement, and Sociodemographic Variables

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the sample every bit a whole and according to sex. Information technology shows statistically significant differences, in some of the emotional intelligence components: intrapersonal: t (2124) = −iv.315, p < 0.001; interpersonal: t (2124) = −4.609; p < 0.001; and adaptability: t (2124) = 2.040; p < 0.05.

There were significant differences betwixt the sexes in the engagement dimensions: vigor (t (2124) = −iii.131; p < 0.01), dedication (t (2124) = −2.843; p < 0.01), and absorption (t (2124) = −iii.532; p < 0.001) with women who scored higher than men, in all cases.

Age was negatively correlated with the emotional intelligence interpersonal factor (r = −0.05; p < 0.01) and positively correlated with stress direction (r = 0.05; p < 0.01). The three appointment dimensions were negatively correlated with historic period (vigor: r = −0.04, p < 0.05; dedication: r = −0.05, p < 0.01; assimilation: r = −0.05; p < 0.01).

Finally, nosotros plant negative correlations betwixt the number of children with the emotional intelligence Interpersonal factor (r = −0.06, p < 0.01), and with the date dimensions of vigor (r = −0.04, p < 0.05) and (r = −0.05, p < 0.05) absorption.

3.2. Components of Emotional Intelligence as Predictors of Date in Nurses

The correlation coefficients we calculated showed that nurses with loftier levels of emotional intelligence also exhibited higher scores in engagement. The correlation assay showed that all of the emotional intelligence components were positively correlated with each of the engagement dimensions, with correlation indices ranging from r = 0.fifteen to r = 0.40, and p < 0.001 in all cases.

Tabular array 2 shows that the regression assay for the appointment dimension vigor gave four models, the quaternary of which demonstrated the greatest explanatory ability, with 22.8% (R 2 = 0.228) of the variance explained by the factors in the model. To ostend the validity of the model, we analyzed the independence of the residuals. The Durbin–Watson D statistic was D = one.964, confirming the absence of positive or negative autocorrelation. The value of t was associated with a probability of fault of less than 0.05 in all of the included variables in the model. The standardized coefficients showed that the variable with the greatest explanatory weight was the interpersonal gene. Lastly, the values of tolerance indicators and VIF suggested the absenteeism of collinearity between the variables included in the model.

The analysis of the dedication component produced four models, the fourth of which demonstrated the greatest explanatory ability, with 21.9% (R 2 = 0.219) of the variance explained. The Durbin–Watson statistic confirmed the validity of the model (D = 1.941). The value of t was associated with a probability of fault of less than 0.05 in all of the included variables in the model. The standardized coefficients indicated that general mood was the strongest predictor of dedication in the sample. The values of tolerance indicators and VIF suggested the absence of collinearity betwixt the variables included in the model.

For the assimilation dimension, the regression analysis produced four models, the 4th of which deemed for 14% of the explained variance (R 2 = 0.140) with D = ane.961, confirming the validity of the model. The value of t was associated with a probability of fault of less than 0.05 in all of the included variables in the model. In this case, the interpersonal component of emotional intelligence was the strongest predictor of absorption. The values of tolerance indicators and VIF suggested the absenteeism of collinearity between the variables included in the model.

The conclusion tree (Figure 1) showed that the interpersonal gene was the all-time predictor of date. Participants with low scores in the interpersonal factor and low adaptability exhibited depression levels of appointment (79.2%). Loftier levels of engagement were present in those with high scores in the interpersonal variable (79.viii%). Finally, the goodness of fit of the model performance could exist seen in its correct classification of 65.seven% of the participants.

3.three. Mediation Models for Estimating the Furnishings on Engagement Dimensions

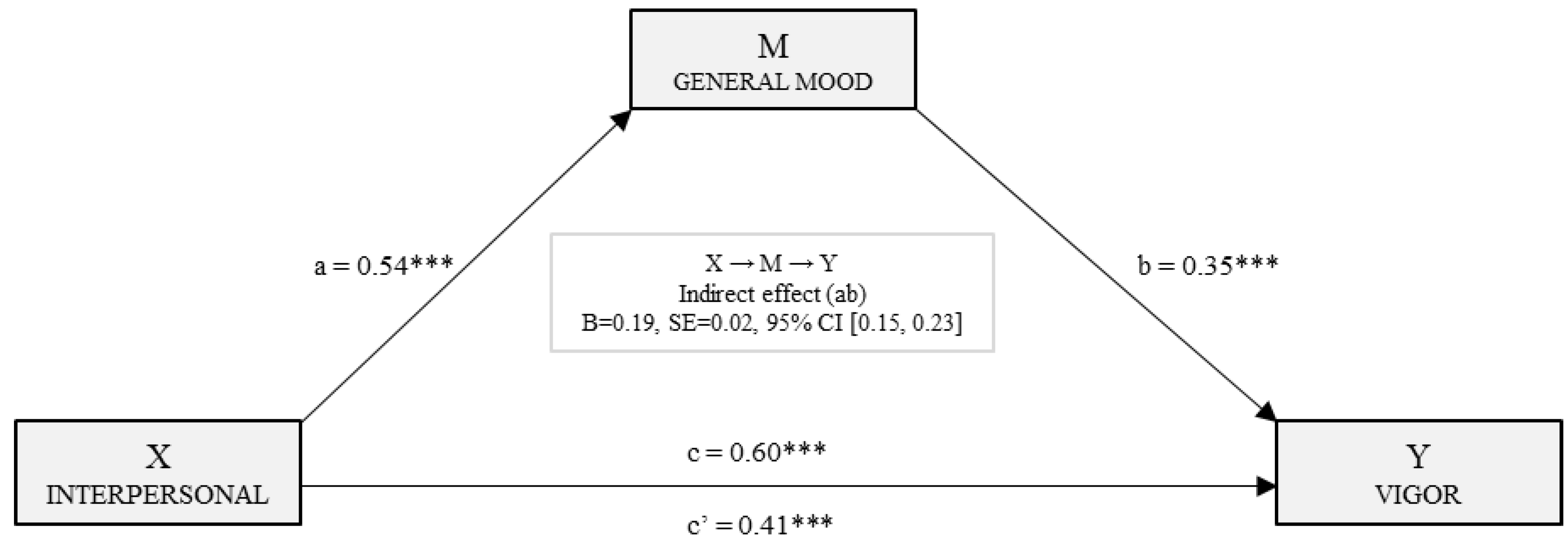

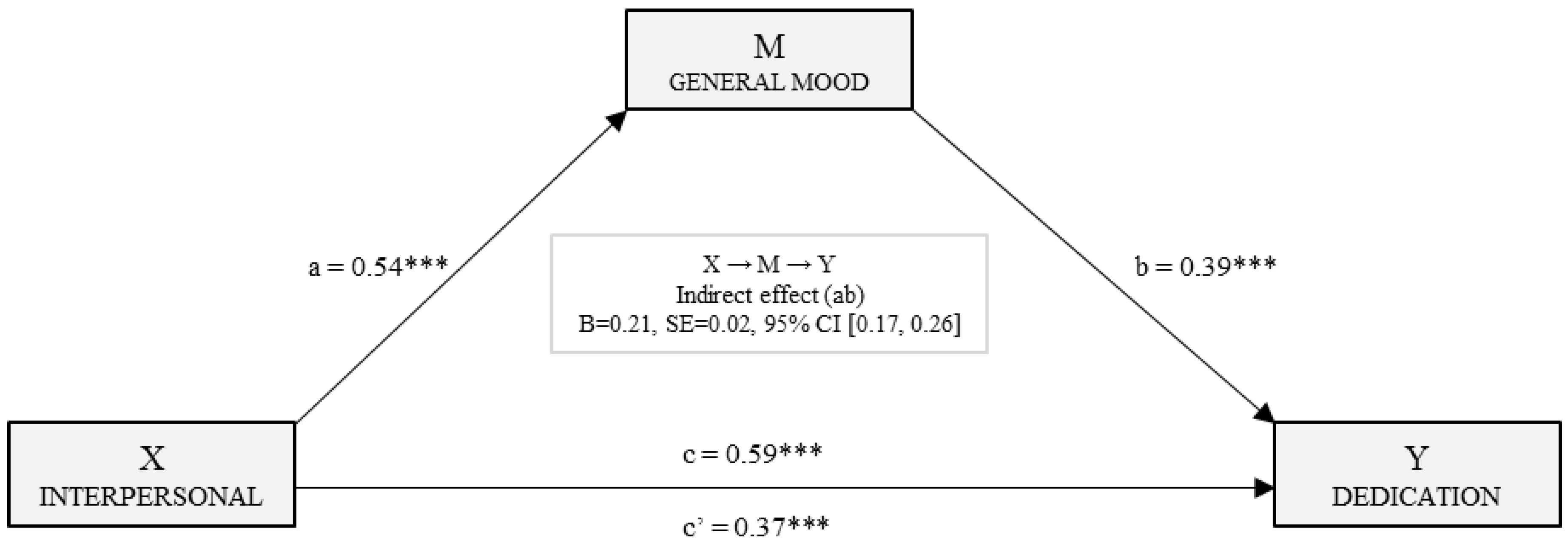

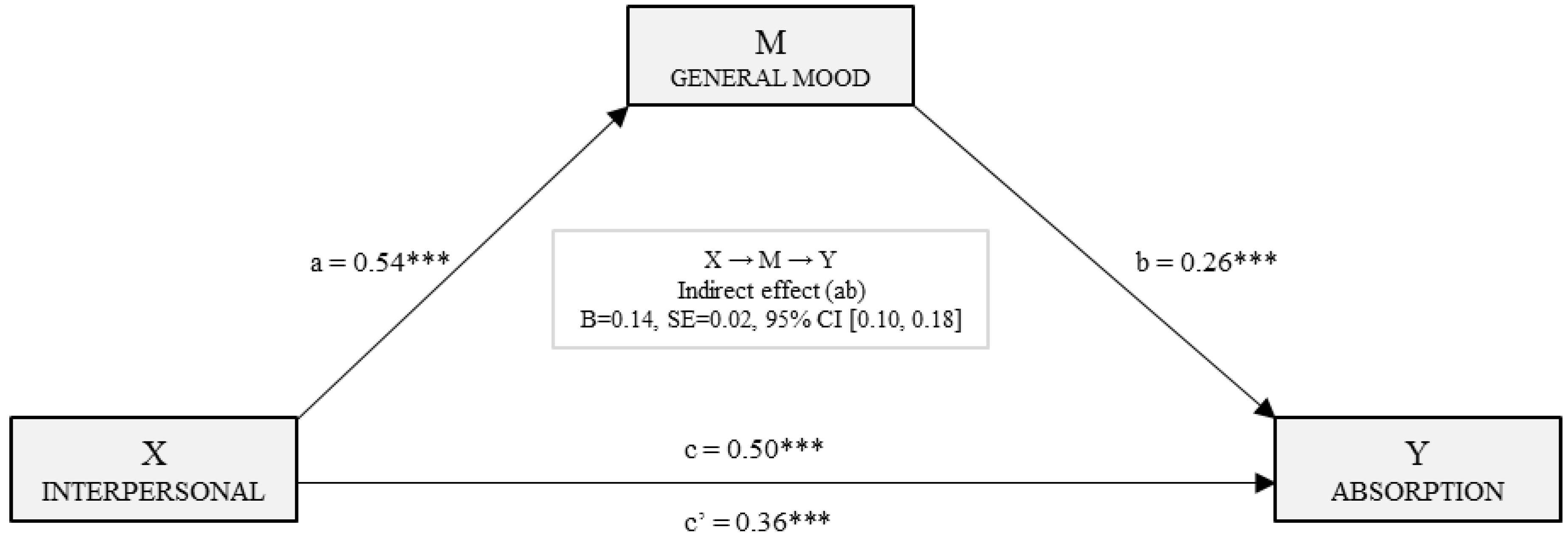

Based on the results of the regression analysis, the emotional intelligence interpersonal factor was taken every bit the contained predictor variable and mood every bit the mediating variable. Thus, 3 elementary arbitration models were computed with the interpersonal factor equally the independent variable in all cases: in the first model, the dependent variable was 'vigor', in the second 'dedication', and in the third, 'absorption' was taken as the dependent variable.

Figure ii shows the simple mediation model for vigor, including the straight, indirect, and total furnishings. In the first identify, information technology may be observed that there was a statistically meaning upshot (B Inter = 0.54, p < 0.001) of the interpersonal factor (X) on mood (1000). The second regression analysis includes the interpersonal factor (X) and mood (M) in the equation. In both cases statistically significant furnishings on the dependent variable were institute (vigor): Yard→Y (B E_ánimo = 0.35, p < 0.001) and X→Y (B Inter = 0.41, p < 0.001). With the third regression analysis, the full outcome of the independent variable (X) on the dependent variable (Y) was estimated. In this case, a statistically pregnant effect of the interpersonal cistron on the vigor dimension of date was establish (B Inter = 0.60, p < 0.001). Finally, the analysis of the indirect effect was carried out using bootstrapping, finding data supporting a significant level (B = 0.19, SE = 0.02, 95% CI (0.15, 0.23)).

Effigy 3 shows the simple mediation model for dedication. Based on the second regression analysis, the effects of the independent variable (interpersonal) and the mediator (mood) on the dependent variable (dedication) were estimated. It may be observed that in both cases, the effect on dedication was statistically significant: (B Inter = 0.37, p < 0.001) and (B E_ánimo = 0.39, p < 0.001). The total upshot of the Interpersonal factor on dedication was meaning (B Inter = 0.59, p < 0.001). Finally, with the analysis of the indirect result with bootstrapping, data extracted supported a significant level (B = 0.21, SE = 0.02, 95% CI (0.17, 0.26)).

Figure 4 shows the simple mediation model for assimilation. With the 2d regression analysis, the issue of the independent variable was estimated taking absorption (Y) as the resulting variable, the consequence of the contained variable (B Inter = 0.36, p < 0.001) and the mediator (B E_ánimo = 0.26, p < 0.001) were estimated, resulting statistically significant in both cases. The total effect of the interpersonal factor on absorption was pregnant (B Inter = 0.50, p < 0.001). Finally, with the analysis of the indirect effects with bootstrapping, a significant effect was found (B = 0.14, SE = 0.02, 95% CI (0.10, 0.18)).

4. Discussion

This study achieved our initial objective by determining the explanatory value of the components of emotional intelligence in date in a sample of nurses.

Nosotros found that women exhibited college levels of emotional intelligence in some emotional intelligence components (interpersonal and intrapersonal). These findings agreed with our second hypothesis, where we expected to observe significant, positive correlations between emotional intelligence and date in nurses. Other research has produced similar results, particularly regarding the relationship betwixt the interpersonal [29,31,32] and the intrapersonal dimensions of emotional intelligence [30,31].

Some studies have plant higher scores in men for the dimensions of stress management [29], full general mood [thirty], and adaptability [32]. However, it is important to note that men were over-represented in the samples in those studies [29,32], and in gild to depict more safely definitive conclusions, information technology would be necessary to have samples that were more evenly balanced between men and women.

Our results showed that historic period was negatively correlated with the interpersonal factor of emotional intelligence and positively correlated with stress management. Harper and Jones-Schenk [33] found that nurses' empathy diminished with age. Kahraman and Hiçdurmaz [34] found a negative correlation betwixt the number of children and the interpersonal factor of emotional intelligence, which was non in agreement with our results.

Nosotros found meaning differences between the gender in all dimensions of appointment, with women scoring higher; this is in line with other research [19]. The iii engagement dimensions were negatively correlated with age, which were like to findings from other studies [sixteen,18,20]. We too saw negative correlations betwixt the numbers of children and the engagement dimensions of vigor and absorption.

We as well achieved our objective of developing an explanatory model of engagement showing that nurses with college levels of emotional intelligence besides scored more highly in appointment, with the interpersonal factor being the greatest predictor of engagement. Other studies support the relationship between the two variables [xi,35,36,37].

Thus, three uncomplicated mediation models were computed with the interpersonal factor every bit the contained variable in all cases: in the starting time model, the dependent variable was vigor; in the second dedication; and in the tertiary, absorption was taken every bit the dependent variable. The assay of the indirect effect was carried out using bootstrapping, finding information supporting a significant level the general mood in all cases.

Our results have pregnant practical implications for the creation of intervention programs and activities to better the performance of nurses in the workplace (e.g., skills training programs for managing emotions in relationships with co-workers, patients). The results should, still, be considered with some intendance due to the following limitations. First, the information were gathered through online questionnaires completed by the nurses and may exist biased as the subjects' responses may be bailiwick to desirability bias. Second, equally the sample we used was very specific and limited to one blazon of profession in the healthcare field, it is possible that the results cannot be generalized to other related healthcare professions. Third, the written report design did not allow united states to make up one's mind whether the date and emotional intelligence scores remained abiding over time. Finally, in Spain, nursing is a predominantly a female profession, which was reflected in the sample, and may be a limitation on the results.

Finally, we are continuing to work on the analysis of elements that encourage worker engagement, and hereafter research should address other variables related to the bailiwick (personality, self-esteem, etc.) and the work environment (such as number of patients dealt with, shift patterns, etc.) in order to continue describing this construct.

v. Conclusions

The results showed that there were significant differences in emotional intelligence and engagement when we looked at the sociodemographic variables in the study (sex activity, age, number of children). These findings supported our first inquiry hypothesis, where nosotros expected to discover differences in emotional intelligence and engagement co-ordinate to sociodemographic variables, although the results constitute in the reviewed literature varied.

Emotional intelligence explained 22.8% of the variability in the engagement dimension vigor, with the interpersonal factor having the greatest explanatory weight. It explained 21.9% of the variability in the dedication dimension, with full general mood being the strongest predictor, and explained 14% of the variability in the absorption dimension, with the interpersonal component being the strongest predictor.

Author Contributions

M.M.M.J., and Thou.C.P.F. contributed to the conception and design of the review. J.J.Grand.50. applied the search strategy. All authors practical the selection criteria. All authors completed the assessment of take a chance of bias. All authors analyzed the information and interpreted data. M.1000.Thou.J., M.C.P.F., and N.F.O.R. wrote this manuscript. Thousand.C.P.F. and J.J.G.50. edited this manuscript. 1000.C.P.F. is responsible for the overall project.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The present report undertaken in collaboration with the Excma. Diputación Provincial de Almería.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Constitution of the World Wellness Organization. Available online: http://world wide web.who (accessed on 22 Apr 2018).

- Adams, Grand.L.; Iseler, J.L. The relationship of bedside nurses' emotional intelligence with quality of care. J. Nurs. Intendance Qual. 2014, 29, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeney, Y.; Fellenz, Chiliad.R. Piece of work engagement as a fundamental driver of quality of care: A written report with midwives. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2013, 27, 330–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, South.; Liu, Y. Impact of professional nursing practice surroundings and psychological empowerment on nurses' work engagement: Exam of structural equation modelling. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sierra, R.; Fernández-Castro, J.; Martínez-Zaragoza, F. Work engagement in nursing: An integrative review of the literatura. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M.East. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, The states, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, Chiliad. Positive Psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Conclusion in Human Beliefs; Plenum: New York, NY, United states of america, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.1000.; Deci, Due east.Fifty. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Existence. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, M.; Lorente, M.Fifty.; Chambel, Grand.J.; Martínez, I.Thousand. Linking transformational leadership to nurses' actress role performance: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.; Campbell, Grand. Work readiness of graduate nurses and the touch on on job satisfaction, work engagement and intention to remain. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiabane, East.; Giorgi, I.; Sguazzin, C.; Argentero, P. Work engagement and occupational stress in nurses and other healthcare workers: The part of organizational and personal factors. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 2614–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunie, K.; Kawakami, N.; Shimazu, A.; Yonekura, Y.; Miyamoto, Y. The human relationship between work appointment and psychological distress of hospital nurses and the perceived communication behaviors of their nurse managers: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 71, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, 1000.; González-Roma, V.; Bakker, A. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A ii sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, Grand.P. Task burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, West.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, One thousand. The measurement of work date with a curt questionnaire: A Cross-national report. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.C.; Ng, S. Measuring Engagement at Work: Validation of the Chinese Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Calibration. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 19, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovakov, A.V.; Agadullina, Eastward.R.; Schaufeli, W.B. Psychometric properties of the Russian version of the Utrecht Piece of work Engagement Scale (UWES-ix). Psychol. Russ. State Art 2017, 10, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkavilli, 1000.; Kulkarni, South.; Doshi, D.; Reddy, South.; Reddy, P.; Reddy, S. Assessment of work engagement among dentists in Hyderabad. Work 2017, 58, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Test Manual for the Utrecht Piece of work Engagement Scale; Utrecht University: Utrecht, Kingdom of the netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Martos, A.; Pérez-Fuentes, 1000.C.; Molero, M.One thousand.; Gázquez, J.J.; Simón, Thousand.M.; Barragán, A.B. Exhaustion y engagement en estudiantes de Ciencias de la Salud. Eur. J. Investig. 2018, 8, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, H.; Yansane, A.I.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Hong, Due north.; Kalenderian, E. Exhaustion and report engagement among medical students at Sun Yat-sen University, Communist china: A cantankerous-exclusive study. Medicine 2018, 97, e0326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liébana, C.; Fernández, M.; Bermejo, J.C.; Carabias, M.; Rodríguez, Chiliad.; Villacieros, Thou. Inteligencia emocional & vínculo laboral en trabajadores del Centro San Camilo. Gerokomos 2012, 23, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, R. The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): Technical Manual; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto, Y.; Teo, Due south.T.T.; Shacklock, K.; Farr-Wharton, R. Emotional intelligence, task satisfaction, well-being and engagement: Explaining organizational delivery and turnover intentions in policing. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 22, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Five.S.; Guerrero, E.; Chambel, M.J. Emotional intelligence and health students' well-being: A two-wave report with students of medicine, physiotherapy and nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 63, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görgens-Ekermans, G.; Brand, T. Emotional intelligence every bit a moderator in the stress-burnout relationship: A questionnaire study on nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, L.; Leggat, Due south.1000.; Donohue, L.; Farrell, G.; Couper, G.Eastward. Emotional rescue: The office of emotional intelligence and emotional labour on well-existence and chore-stress among community nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, seventy, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerits, L.; Derksen, J.J.; Verbruggen, A.B. Emotional intelligence and adaptative success of nurses caring people with mental retardation and severe beliefs problems. Ment. Retard. 2004, 42, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; AsgharNejad Farid, A.A.; Kharazi Fard, K.J.; Khoei, Northward. Emotional intelligence of dental students and patient satisfaction. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 14, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dusseldorp, L.R.; van Meijel, B.K.; Derksen, J.J. Emotional intelligence of mental wellness nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Light-green Version]

- Arteche, A.; Chamorro-Premuzic, T.; Furnham, A.; Crump, J. The Relationship of Trait EI with Personality, IQ and sex in a Britain sample of employees. Int. J. Sel. Appraise. 2008, 16, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, M.M.; Jones-Schenk, J. The emotional intelligence contour of successful staff nurses. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2012, 43, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman, N.; Hiçdurmaz, D. Identifying emotional intelligence skills of Turkish clinical nurses according to sociodemographic and professional variables. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mérida-López, Southward.; Extremera, Northward.; Rey, L. Contributions of Work-Related Stress and Emotional Intelligence to Teacher Engagement: Additive and Interactive Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, C.; Guo, B.; Zhao, L.; Lou, F. The touch of emotional intelligence on piece of work date of registered nurses: The mediating role of organizational justice. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2115–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrosa, E.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R. Role stress and personal resources in nursing: A cross-sectional study of burnout and engagement. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nel, J.A.; Jonker, C.S.; Rabie, T. Emotional intelligence and wellness amid employees working in the nursing environs. J. Psychol. Afr. 2013, 23, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez, J.J.; Mercader, I.; Molero, Thousand.M. Brief Emotional Intelligence Inventory for Senior Citizens (EQ-i-M20). Psicothema 2014, 26, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R.; Parker, J.D.A. Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version (EQ-i:YV): Technical Manual; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Assay: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, The states, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1. Regression and nomenclature tree for appointment.

Effigy 1. Regression and nomenclature tree for engagement.

Figure 2. Simple mediation model of mood on the relationship betwixt the interpersonal cistron and the vigor dimension of engagement. (Note: ***p < 0.001).

Figure two. Simple mediation model of mood on the relationship between the interpersonal cistron and the vigor dimension of engagement. (Note: ***p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Uncomplicated mediation model of mood on the relationship between the interpersonal gene and the dedication dimension of engagement. (Note: ***p < 0.001).

Figure iii. Simple mediation model of mood on the relationship betwixt the interpersonal cistron and the dedication dimension of date. (Note: ***p < 0.001).

Figure four. Uncomplicated mediation model of mood in the relationship between the interpersonal cistron and the absorption dimension of engagement. (Annotation: ***p < 0.001).

Figure 4. Simple mediation model of mood in the human relationship betwixt the interpersonal factor and the absorption dimension of engagement. (Note: ***p < 0.001).

Table ane. Emotional intelligence and date. Descriptive statistics and t-examination by sexual practice.

Table 1. Emotional intelligence and engagement. Descriptive statistics and t-test by sexual activity.

| Total due north = 2126 | Men n = 321 | Women n = 1805 | t | Sig. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | Chiliad | SD | ||||

| Emotional Intelligence | Intrapersonal | 2.62 | 0.698 | 2.46 | 0.690 | 2.65 | 0.696 | −four.315 *** | 0.000 |

| Interpersonal | three.06 | 0.501 | 2.94 | 0.530 | iii.08 | 0.493 | −iv.609 *** | 0.000 | |

| Stress Direction | three.25 | 0.567 | 3.26 | 0.569 | 3.24 | 0.567 | 0.380 | 0.704 | |

| Adjustability | two.91 | 0.526 | 2.96 | 0.527 | 2.90 | 0.526 | 2.040 * | 0.042 | |

| General Mood | 3.08 | 0.599 | 3.eleven | 0.607 | 3.08 | 0.598 | 0.871 | 0.384 | |

| Date | Vigor | 3.85 | 0.771 | three.72 | 0.808 | 3.87 | 0.762 | −3.131 ** | 0.002 |

| Dedication | 4.07 | 0.794 | three.94 | 0.884 | 4.09 | 0.775 | −2.843 ** | 0.005 | |

| Assimilation | 3.52 | 0.800 | three.38 | 0.849 | iii.55 | 0.788 | −three.532 *** | 0.000 | |

Tabular array 2. Multiple stepwise linear regression model (N = 2126).

Table 2. Multiple stepwise linear regression model (N = 2126).

| Vigor | Model | R | R two | Adjusted R 2 | Change Statistics | Durbin Watson | ||||

| Standard Error of Estimation | Alter in R 2 | Change in F | Sig. of Alter in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.397 | 0.158 | 0.158 | 0.708 | 0.158 | 398.401 | 0.000 | 1.964 | ||

| 2 | 0.465 | 0.216 | 0.216 | 0.683 | 0.058 | 158.160 | 0.000 | |||

| iii | 0.473 | 0.224 | 0.223 | 0.680 | 0.008 | xx.508 | 0.000 | |||

| 4 | 0.477 | 0.228 | 0.226 | 0.678 | 0.004 | 10.834 | 0.001 | |||

| Model 4 | Not-standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | std. error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.134 | 0.118 | 9.593 | 0.000 | ||||||

| General Mood | 0.264 | 0.033 | 0.205 | 8.104 | 0.000 | 0.570 | 1.756 | |||

| Interpersonal | 0.364 | 0.037 | 0.236 | ix.953 | 0.000 | 0.647 | 1.547 | |||

| Stress Management | 0.128 | 0.028 | 0.094 | 4.629 | 0.000 | 0.879 | 1.138 | |||

| Adaptability | 0.128 | 0.039 | 0.087 | iii.292 | 0.001 | 0.519 | 1.928 | |||

| Dedication | Model | R | R 2 | Adjusted R 2 | Change Statistics | Durbin Watson | ||||

| Standard Mistake of Estimation | Alter in R 2 | Change in F | Sig. of Change in F | |||||||

| 1 | 0.407 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.726 | 0.165 | 420.764 | 0.000 | ane.941 | ||

| two | 0.458 | 0.210 | 0.209 | 0.706 | 0.044 | 119.178 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | 0.466 | 0.217 | 0.216 | 0.703 | 0.007 | xix.051 | 0.000 | |||

| 4 | 0.467 | 0.219 | 0.217 | 0.703 | 0.002 | 4.800 | 0.029 | |||

| Model 4 | Non-Standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | std. error | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Abiding) | 1.391 | 0.122 | xi.449 | 0.000 | ||||||

| General Mood | 0.336 | 0.031 | 0.253 | 10.688 | 0.000 | 0.655 | 1.526 | |||

| Interpersonal | 0.354 | 0.035 | 0.223 | 10.026 | 0.000 | 0.745 | 1.343 | |||

| Stress Direction | 0.130 | 0.029 | 0.093 | iv.510 | 0.000 | 0.875 | one.142 | |||

| Intrapersonal | 0.054 | 0.025 | 0.048 | two.191 | 0.029 | 0.774 | 1.292 | |||

| Assimilation | Model | R | R 2 | Adjusted R 2 | Modify statistics | Durbin Watson | ||||

| Standard Error of Interpretation | Modify in R 2 | Change in F | Sig. of Change in F | |||||||

| ane | 0.316 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.759 | 0.100 | 236.011 | 0.000 | 1.961 | ||

| 2 | 0.362 | 0.131 | 0.130 | 0.746 | 0.031 | 76.359 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | 0.369 | 0.136 | 0.135 | 0.744 | 0.005 | 12.570 | 0.000 | |||

| 4 | 0.374 | 0.140 | 0.138 | 0.743 | 0.003 | eight.322 | 0.004 | |||

| Model four | Non-Standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||||

| B | std. fault | Beta | Tol. | VIF | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.361 | 0.128 | x.598 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Interpersonal | 0.325 | 0.037 | 0.204 | 8.725 | 0.000 | 0.745 | ane.343 | |||

| General Mood | 0.202 | 0.033 | 0.152 | 6.093 | 0.000 | 0.655 | 1.526 | |||

| Intrapersonal | 0.098 | 0.026 | 0.086 | 3.743 | 0.000 | 0.774 | 1.292 | |||

| Stress Management | 0.088 | 0.030 | 0.062 | 2.885 | 0.004 | 0.875 | 1.142 | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access commodity distributed nether the terms and weather of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/).

burrellfroccattled.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/9/1915/htm

0 Response to "Studies Using Emotion as a Dependent Variable Peer Review"

Post a Comment